A British company is developing a space-based “factory” to produce materials for quantum computers, AI data centers and defense infrastructure.

Space Forge, located in Cardiff, Wales, has reached a key milestone on its way to creating ultra-high-quality crystal “seeds” in space for the manufacture of semiconductors back on Earth, where they could be used in communications infrastructure, computing, and transport.

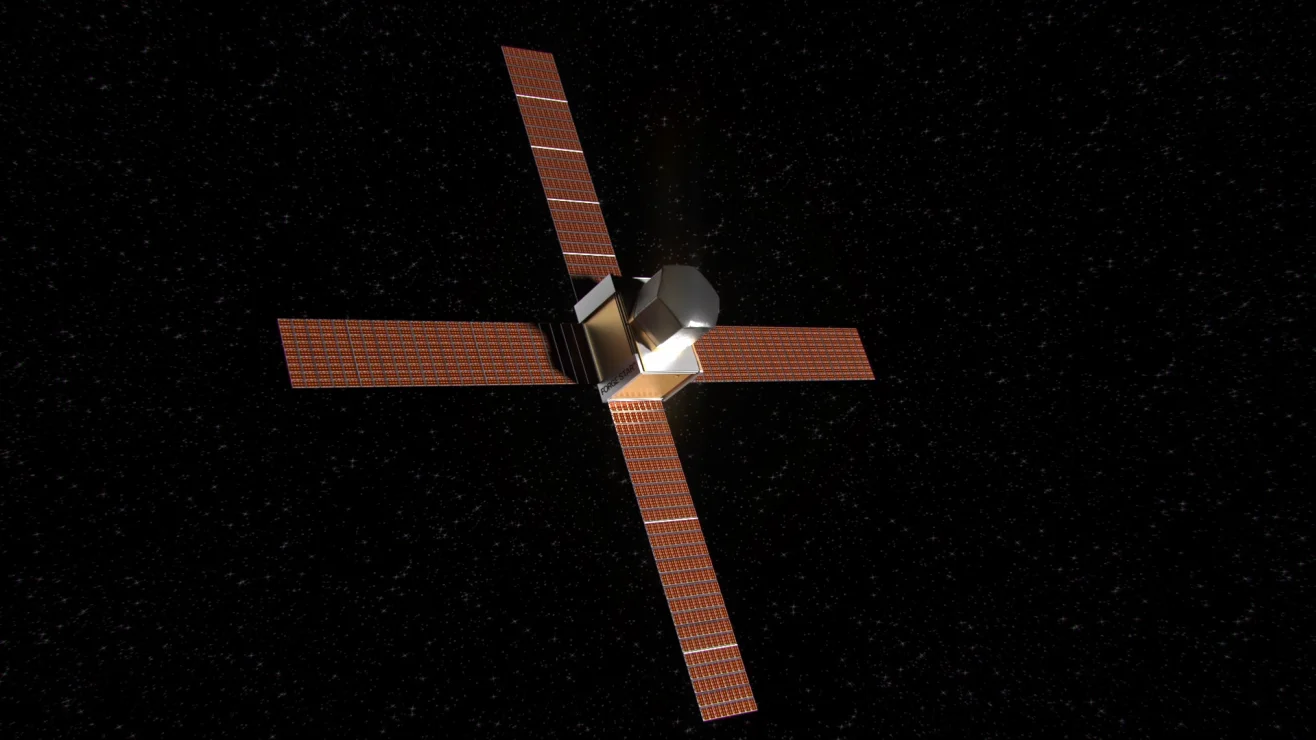

In June 2025, it launched a microwave-sized factory satellite called ForgeStar-1 into orbit on a SpaceX rocket, and was able to generate plasma — gas heated to 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,832 Fahrenheit) — which would allow the production of advanced crystals in the future.

“Space offers an unparalleled industrial base compared to Earth,” says Space Forge CEO and co-founder Joshua Western.

When semiconductor materials are manufactured under conditions of microgravity the atoms they consist of are arranged more regularly, Western explains.

He adds that the vacuum of space reduces the likelihood of contamination, allowing for the production of “semiconductor crystals that are hundreds, if not thousands, of times higher in purity compared to those that can be produced on the ground.”

The combination of a more-ordered atomic structure and fewer impurities enables “huge gains” in the efficiency of the semiconductor the crystals are used to make, he explains.

“ForgeStar-1 is about proving the manufacturing tool,” says Western, adding that Space Forge hopes to send a commercial production system into orbit within two years.

The company is looking to sell its materials to businesses that require semiconductors capable of operating at very high powers. “Our core markets right now are aerospace and defense and telecommunications and data,” says Western.

But back on Earth, there are obstacles for Space Forge. “Regulation, by far, has been the biggest challenge,” says Western. “We’re a business that’s trying to do something that doesn’t yet exist.”

He says that while ForgeStar-1 was built in just seven weeks, obtaining the license to launch it took two and a half years.

And because no country has sovereignty in space, it is uncertain how the materials are to be taxed when returned to Earth, says Western. “What was produced wasn’t made in the country it landed in. But neither was it made in any other country.”

The question of taxation is no small issue, given the value of the materials Space Forge hopes to manufacture in space.

Where the company will be producing high-quality versions of compounds that already exist on Earth, Western says these could be worth in the low tens of millions of dollars per kilogram. But he adds that manufacturing in space “enables hundreds of new material combinations” previously only theorized, which will be valued “in the higher tens of millions.”

But will companies be willing to pay?

Down to Earth

According to market analysis by Deloitte, the global semiconductor market grew by 22% in 2025 and is expected to be a $1 trillion industry by 2027, driven largely by a boom in AI infrastructure.

“It’s really these kinds of cutting-edge technologies that need the highest quality material,” says Jessica Frick, a former researcher at Stanford University’s XLab, which specializes in manufacturing both in and for space, and who is not involved with Space Forge.

Frick, who has since co-founded Astral Materials, an in-space manufacturing company based in the US, says that while “there is a growing demand for ultra-high-quality materials,” would-be space manufacturers need to prove themselves to potential buyers.

“Until the industry can show a reliable, high-cadence return from low orbit of these materials, the barrier of adoption will be very high,” she says.

Frick is confident that with a growing number of rocket launches from private companies like SpaceX, accessibility to space will only improve.

But she says that the schedule of return flights to Earth, on which space manufacturing companies could piggyback their materials and factories, is much lower. “Getting our products back down to Earth is something that’s a massive challenge,” says Frick.

Nevertheless, given the current rate of expansion of the space industry she thinks it could be possible to have flights returning to Earth monthly within five years.

Space Forge is developing a heat shield that will be used to return the factory satellite and materials to Earth, by functioning like a parachute, while protecting them from the intense temperatures the spacecraft will experience as it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere.

“It is best described as Mary Poppins, but for space. It’s basically a space-grade umbrella that deploys at the end of a mission and it allows us to effectively float back from orbit all the way down to the ground,” says Western.

He hopes the technology will be a step toward enabling a more rapid and reliable delivery of the materials back to Earth.

Hurdles are high

Western says that the fully functioning factories Space Forge intends to launch will be roughly the size of a large washing machine, weighing around 100 kilograms (220 pounds), and that each will be capable of producing enough material for 10 million semiconductors within a few weeks of activation.

Launching ForgeStar-1 cost £250,000 ($342,000) and Western says that even factoring in that expense, the cost of producing crystals at their developmental “seed” stage in space is comparable with that of Earth-based processes. He adds that solar energy in space — which will power the factories — is abundant and “free.”

Matthew Weinzierl is senior associate dean at Harvard Business School and has written on the business and economics of space. He cautions that the hurdles to in-space manufacturing are high.

“I don’t foresee any widescale commercial viability in the next decade,” he says. But he adds that, with the costs of operating in space decreasing, it’s “inevitable” that manufacturing some products in space will be economically viable.

“It’s worth experimenting with and investing in these possibilities. We can learn techniques by working in space that we’d never learn with terrestrial experimentation alone,” says Weinzierl.

Western says that Space Forge has so far raised $30 million in capital from investors around the globe, including the NATO Innovation Fund.

He expects the conclusion of the ForgeStar-1 mission in a few months, after which the company will test its heat shield in space for the first time.

“My hope is that in 10 years’ time, what I do is boring,” says Western. “The day that somebody gets told that their phone or their laptop is made using a space-made chip, and that doesn’t excite them, then I know that we’ve succeeded.”